Dividing the Reservation

By: Sara Stolz Swisher Nestled on the Camas

Prairie, roughly seven miles northeast of Cottonwood, is the community

of Greencreek, Idaho. Homesteaded in 1895, Greencreek is one of several

communities located within the boundaries of the Nez Perce Indian

Reservation. How is that possible? The answer is the Dawes General

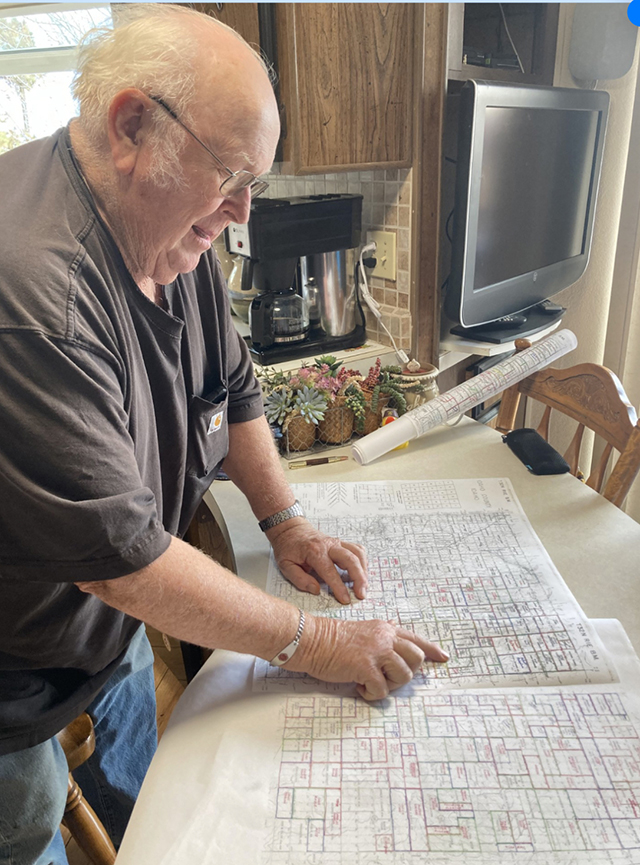

Allotment Act of 1887 (Dawes Act).The Nez Perce people originally occupied an area that included parts of what are now Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. They lived and migrated throughout this area as well as areas of present-day Montana and Wyoming. In 1853, Washington’s first territorial governor, Isaac Stevens, arrived in the territory. He had three tasks: create a government for the new territory; survey a route for a potential transcontinental railroad (what eventually became the Northern Pacific); and serve as superintendent of Indians Affairs. When Stevens arrived in the territory, what we know as Greencreek was part of Washington, as was all of current Idaho north of Fenn. The federal government was interested in acquiring legal rights to western lands from Indians. It anticipated the time when the West would face an influx of settlers. The government needed the ability to provide legal land access to settlers, as well as land upon which to build infrastructure like roads and railroads. In his duty as Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Stevens entered into a number of treaties with Northwest tribes, including the Nez Perce Treaty of 1855. All 56 Nez Perce bands signed the Treaty, resulting in a reservation of 7.5 million acres with the right to continue to hunt and fish in their traditional grounds. After gold was found along the Clearwater in 1860, miners rushed into north-central Idaho, trespassing on the Nez Perce’s 1855 Treaty land. To legally justify the intrusion, the federal government coerced the Nez Perce into negotiating another treaty in 1863. It shrank the reservation borders by 90% to ~750,000 acres with land located in what are now Clearwater, Idaho, Lewis and Nez Perce Counties. Many Nez Perce refused to sign what they called the “Thief Treaty,” and dissatisfaction led directly to the War of 1877. The Dawes Act that followed in 1887 gave the president the power to subdivide reservation lands across the United States. Every Indian [Nez Perce] “head of a family received 160 acres, each single person over 18 and orphans received 80 acres. All other single persons under 18 born prior to the allotment order, were assigned 40 acres.” The man in charge of surveying and issuing land allotments turned out to be a woman named Alice Fletcher. She helped write the Dawes Act and was one of the first female Federal Indian Agents. She oversaw the land allotments to the Omahas and Winnebagos prior to supervising the Nez Perce allotments from 1889-1892. Fletcher concluded her work in 1892, and on November 8, 1895, President Grover Cleveland issued Proclamation 381. It declared that unallotted Nez Perce Reservation ground was open for settlement. The Lewiston Tribune (Tribune) reported that in the days leading up to the November 18,1895 opening, “the land office in Lewiston was besieged with landseekers. They formed in a long line and remained after the office closed. Additional clerks were required and the office stayed open at night.” Applicants were required to be 21 years of age or the head of household, which allowed women to own land. They were also required to file an affidavit and pay a $12.00 processing fee. The Tribune further reported that at noon on the day of the rush, “heads began bobbing up all over the former reservation and 3,000 persons asserted their right to possession of 2,500 tracts of Nez Perce Land.” The paper went on to say, “men and women were afoot, others were on horseback. Scores drove rigs pulled by one, two and four horses – any way to get to their selected allotment first. Horses dropped from exhaustion and others were snatched to take their place. This will probably result in horse stealing charges being preferred by disgruntled land seekers.” It was a wild affair. “Men were on the verge of madness…Loud oaths were heard and fist fights were common.” Settlers raced to claim allotments of up to 160 acres of land. Placing a stake was not sufficient. A “foundation” consisting of four boards nailed together at the ends to form a 12 square foot outline was required. According to Greg Stolz, local Greencreek historian and grandson of 1895 homesteader Edwin Stolz, homesteaders were not required to live on their claims the first winter because they were staked so late in the year. Starting the following spring however, they had to live on the claims full-time for 5 years. During this period, improvements had to be made including building a cabin and animal fence, and planting an orchard and garden. After 5 years, homesteaders returned to the Lewiston land office with two witnesses who would testify that they had known the claimant for 5 years and that improvements had been made to the claim. This process became known as “proving-up.” Once done, and a $6.00 filing fee paid, the homesteader was issued a land patent, giving him/her ownership of the property. Stolz explained that not all available land was claimed immediately, and that a significant portion was sold or traded either before or just after the five-year period. He estimates that approximately 60 families homesteaded in what is now known as Greencreek in 1895, and that approximately 60% of those homesteads were sold once they were “proven-up.” Today, a total of seven of Greencreek’s 1895 homesteading families still live and work on their 1895 homesteads. Greencreek is just one of many communities born from the Dawes Act. The Act divided the Nez Perce Reservation, fueled a land rush, and resulted in a checkerboard of public, private and tribal land in Clearwater, Idaho, Lewis and Nez Perce Counties. More than 70% of the land “reserved” in the 1863 treaty passed into non-Nez Perce control, and by 1910, 1,500 Nez Perce and 30,000 non-Indians lived on the reservation. It is a fascinating chapter in Idaho’s history whose story is worth remembering. **Edited by former Idaho State Historian, Keith Petersen  Greencreek historian, Greg Stolz, with the map he and Louis Stubbers created for the community's 1995 Centennial. The map denotes the names of Greencreek's original 1895 homesteaders in red ink, with the names of the 1995 owners in black. The map is now part of the museum's collection.  Nez Perce Reservation boundary marker located two miles north of Cottonwood on Highway 95.

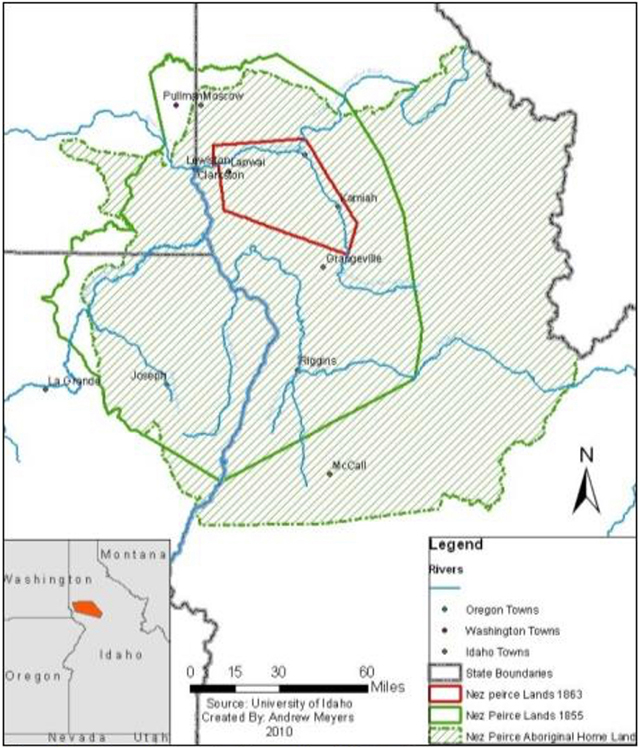

Map of the Nez Perce Reservation Boundaries, 1855 to 1863 in solid green and the boundaries since 1863 in red. |

|